A recent visit of Dendera enticed me to try to read those flamboyant inscriptions around the temple. All the more since the IFAO guide of Dendera told me that they contained descriptions of the whole temple - and the subject of “meta” information in Egyptian texts is a topic which deeply interests me.

Some “ptolemaic” inscriptions are relatively easy to read, because either their content is dictated by their context, or because they use only a handful of unusual signs and/or values, or relatively transparent puns like a-anx-E86 for dꞽ ꜥnḫ mꞽ Rꜥ.

Now, the dedicatory inscriptions of Dendera don't belong to this category. They are monumental, quite impressive in the variety of the depicted objects, and they use lots of unusual signs and values.

I was thus very happy to find Sylvie Cauville's article “Les inscriptions dédicatoires du temple d’Hathor à Dendera”, Bulletin de l’Institut français d’archéologie orientale 90, 1990, pp. 115–133, which gives a detailled translation of the dedicatory inscriptions.

Reading this article with profit requires some knowledge of ptolemaic hieroglyphs, and access to a number of resources (for instance, the numeric values of some signs are not always easy to find).

As many people might be interested in understanding how this inscription works, I have decided to give a full explanation of the short passage above, and a kind of reading guide for the whole article.

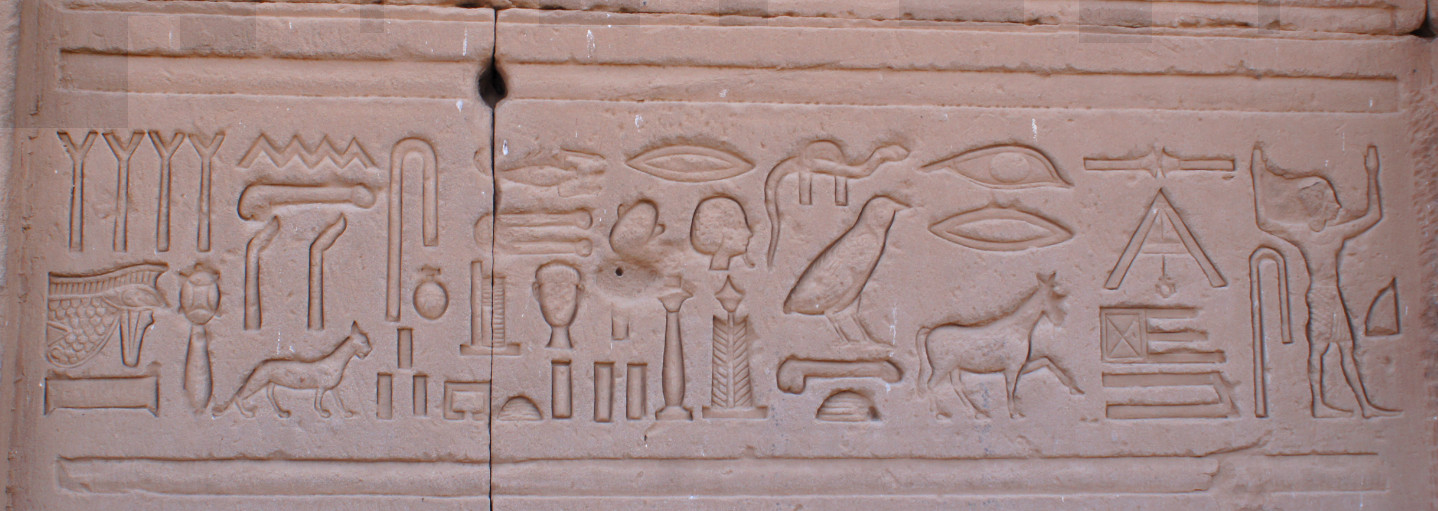

Our picture

This picture is a part of the dedicatory inscription from the western outer wall of the pronaos (Dendara XV, p. 269 for the text, and Dendara XV, plates, p. 324 for another picture). Both can be freely downloaded from the [IFAO web site]().

The text in our picture is not the most complex part of the dedicatory inscriptions. But I guess the unusual U97 mason level sign, and its location, makes this particular passage very well known, as I have seen many pictures of it.

Unfortunately, this particular passage is not translated in S. Cauville's article, but her text gives enough information to understand most of the signs - and in S. Cauville full translation and comment of the Dendera texts1 solved the few problems which remained.

The text describes the pronaos of temple. Its reading is made easier by the repetitive nature of the description. Moreover, the text is almost written twice (with variants): once on the eastern outer wall, and once on the western outer wall (whence our passage originates).

Here is a detailled analysis of the text:

N29-A28-S29-O34:U97-S32:Aa15-D4:D21-E6C-V21-G43-D52:X1-D21:D1*Aa2-O28-O206-Z2A-L19:V13-D2:Z1-Q1:X1*O1-S29-W24-Z2A-N35-D52:T14*T14-E90-O30-O30-O30-O30-F32-D10A:N1

-

The beginning is actually very regular hieroglyphs: N29-A28-S29 for qꜥ=s, “its height” (referring to the pronaos, i.e. the part with the hypostyle hall and the huge Hathor-headed columns).

-

Now, a bit more complex, because U97 (U97) is unusual, but not that weird. It has the value sḫḫ, which means width;

-

S32 is normally sꞽꜣ; but in ptolemaic texts, according to the consonantal principle, which states that a sign which has only one strong consonant can be used as an alphabetic sign for this consonant, it writes the suffix pronoun ⸗s; this value is quite common in the Dendera dedicatory inscriptions, as far a I can tell from reading Sylvie Cauville's article;

-

M-ir-r has its regular reading m ꞽr(w) r for “as something done according to...”;

-

E6C has the value nfr, perfect, good - it's a value relatively usual for horses signs in ptolemaic texts;

-

V21-G43-D52:X1-D21:D1*Aa2 : mḏ wm.t r tp-ḥsb. The translation is a bit unsecure here; My first interpretation was mḏ.w mtꞽ r tp-ḥsb, (its) foundations are exact according to the specifications. However I was wrong.

Mḏ.t is normally the bottom part of the wall, and is usually used in the expression mḏ.t r tp⸗f, from its bottom to its top, to indicate the height of something. It's also found in the expression mḏ.t s r mtr, its depth? fundations? being exact. It's not too far from my first interpretation. But it doesn't account for the w nor for the spelling of mtr. Sylvie Cauville reads the w as the beginning of the second word, wm.t, which means thick, thickness.2

-

O28-O206-Z2A ꞽwn.w, columns; regular hieroglyphic orthography, with the determinative O206;

-

L19:V13 wḥꜥ.tꞽ : according to Kurth, o.c. p. 727, the old perfective can have quite a few different endings, including ti (here T), including for the third person masculine plural. In Demotic, the endings .k (< former .kw), .w and .tꞽ can be found regardless of the subject. Janet Johnson writes “thus the ending was simply marking the form as a qualitative”3; this phenomenon already appears, albeit less extreme, in Late Egyptian4. The verb wḥꜥ is often used for laying out (foundations) ; here I would translate simple placed or something like that; Actually S. Cauville has interpreted this word as a spelling of wꜣḥ, which is even more straightforward. The original wḥꜥ can quite easily be a spelling of wꜣḥ, because both “ꜥ” and “ꜣ” can fall in Ptolemaic orthography (I think Fairman says that the presence of ḥ is a factor in this case).

-

D2:Z1-Q1:X1*O1-S29-W24-Z2A ḥr s.t=sn, regular hieroglyphic orthography, except for nw for n in =sn

-

N35-D52:T14*T14 m mt(r)ꞽ the N35 can be understood either as n or as m (n for m is quite usual already in Late Egyptian) ;

-

E90 the cat sign has the reading mꞽ, from mꞽw, and simply writes the preposition mi-i;

-

O30-O30-O30-O30 sḫn.t or sḫn.t ꞽfd, the four pillars of the sky;

-

F32 writes the preposition ẖr,; it's not very surprising. Final r falls as early as Middle Egyptian (see S29-G36:D21-M17-A2, swr > swꞽ ). Hence a single ẖ can be used to write ẖ(r);

-

D10A:N1 wḏꜣ.t, the sky, heaven, roof of temple (Wilson, p. 288)

Hence, we have the following (rather mundane) translitteration and translation:

qꜥꜥ⸗s sḫḫ⸗s m ꞽr(w) r nfr mḏ wmt r tp-ḥsb ꞽwnw wḥꜥ.tꞽ ḥr s.t⸗sn mꞽ sḫn.t wḏꜣ.t

Its length and width are made to perfection; the depth of its foundations and the thickness of its walls match the specifications. Its columns stand precisely in their (appointed) places, like the four pillars that uphold the sky.

Other parts of the text give more precise information, such as the name of the rooms, their dimensions, and their uses.

Some hints and tips for reading Sylvie Cauville's article

Sylvie Cauville provides a facsimile of the inscriptions, along with a transliteration, translation, and commentary. The article is aimed at scholars familiar with the Ptolemaic signs, which means that the only the complex sign values are discussed and explained.

The following text does not in any way pretend to exhaustivity, far from it. The idea is to give a bit of clues to ease the reading.

Bibliography

There are lots of resources for working on ptolemaic texts. I will list only the most useful to start working on this stage of the language:

- S. Cauville, Dendara. Le fonds hiéroglyphique au temps de Cléopâtre, Paris, 2001: gives a list of sign values from Dendera in a practical format;

- H.W. Fairman, « An Introduction to the Study of Ptolemaic Signs and their Values », BIFAO 43, 1945, p. 51‑138: one of the classical works. An interesting feature is that you can download it for free :-)

- H.W. Fairman, « Notes on the Alphabetic Signs Employed in the Hieroglyphic Inscriptions of the Temple of Edfu », Annales du Service des Antiquités de l’Égypte 43, 1943, p. 191‑310: the other classical study; a bit harder to find;

- Kurth, Einführung ins Ptolemäische: eine Grammatik mit Zeichenliste und Übungsstücken, Hützel, 2007; an encyclopedic study in two volumes;

- C. Leitz, Quellentexte zur ägyptischen Religion, Einführungen und Quellentexte zur Ägyptologie Bd. 2, Münster, 2004; contains a short introduction, a chrestomathy of ptolemaic texts, a sign list and a vocabulary. Plus, it's relatively inexpensive (around 20 euros).

- S. Cauville, Dendara. 15: Traductions. Le pronaos du temple d’Hathor: plafond et parois extérieures, Orientalia Lovaniensia analecta 213, Leuven, 2012.

Among other ressources, the IFAO has released most of its temple publications. Serge Sauneron, L'écriture figurative dans les textes d'Esna (Esna VIII) is a classic, but its focus is a subsystem of ptolemaic writing, in which the meaning of the text is almost completely given by the context, which allows the text composer to choose the signs for their figurative - and not linguistic - values. It's very worth reading, but is definitly not the way to start learning ptolemaic.

Knowledge of the texts

Ptolemaic spelling can be more or less regular. If you look at the Rosetta Stone, the spellings are not that weird.

Most of the time, the priests chose to “play” with the system when the meaning of the inscription was clear because of its context. The name and epithets of gods, the legends of offering scenes, and passages of well known texts are the primary targets of their scribal feats. In this respect, knowing parallel or similar inscriptions, usual names of a local deity, etc. is quite important. I suspect that a book like the LÄGG5 can be quite helpful for this. Leitz, Quellentexte zur ägyptischen Religion, gives a panel of typical texts.

Oh, and use dictionaries. I was at loss at some point with the (rather transparent) spelling wDAt:pt, because I did not bother to check for wḏꜣ.t in the dictionary (mostly the Wörterbuch, or Wilson). Given the context and the determinative, I was more or less sure it was a name of the sky, but instead of hitting the dictionary to see if wḏꜣ.t fitted, I was trying to find a way to match the spelling with more usual words, like p.t or nn.

Text layout

The text layout in the Dendera dedicatory inscriptions is not always easy to follow. If you look at our inscription, the group which starts with r-tp-ḥsb could possibly be read as either D21:D1*Aa2-O28-O206-Z2A-L19:V13-D2:Z1-Q1:X1*O1-S29-W24-Z2A (as two short text columns), or as D21:D1*Aa2-L19:V13-O28-O206-Z2A-D2:Z1-Q1:X1*O1-S29-W24-Z2A, reading first horizontally, then vertically.

Hence, when the text makes no sense, try to see if you followed the correct reading order.

Numbers

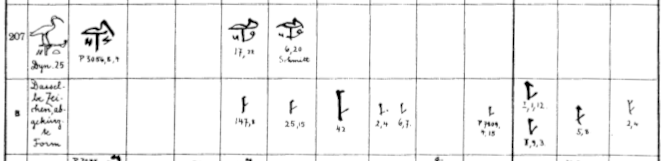

In most cases, numbers are written with the usual system: 100-10-2 for 112. The Dendera dedicace often uses other signs, like sbA for “5”, or tp for 7 (because the head has seven openings). To make things more complex, those signs don't behave as digits. You actually need to sum their values, and signs for the units might add to tens.

One can find “10” written tp-Z1-ra-N10A for 7 + 1 + 3, “8” can be written wp-sbA-Z1, 2 + 5 + 1, and 26 written G5-tp-G26A-Z1, 10 + 7 + 8 + 1.

This is of course somehow disturbing. But:

- the number of signs with numerical values is relatively small;

- the context helps a lot. If you have mH:a, mḥ, cubits, you usually expect it to be followed by a number of cubits.

| Sign(s) | value | comment |

|---|---|---|

| Sw | 1/2 | gs |

| gs | 1/2 | gs (not really ptolemaic) |

| T21A | 1 | variant of wa |

| ra | 1 | there is one sun |

| wp | 2 | two horns |

| ra-N10A | 2 | |

| W4 | 4 | |

| sbA | 5 | |

| tp | 7 | seven holes of the head |

| s-s | 8 | hieratic confusion |

| G26A | 8 | Ibis/Thot/ogdoag/8 |

| E35 | 8 | Thot/ogdoag/8 |

| F58 | 8 | the sign has also the value ḫmnw |

| N8 | 9 | value psḏ |

| mA | 9 | |

| G5 | 10 | |

| Z9 | 30 | |

| p | 60 | |

| O42 | 80 | |

| N89 | 100 | |

| M111 | 1000 | variant of xA |

| qmA | 10000 | confusion with Dba |

| I7 | 100000 | confusion with Hfn |

Repeating a sign can have a numeric value: G30 for 3.

“New” regular signs

A few signs appear or become much more common in the Late Period. Among those:

| Sign(s) | value | comment |

|---|---|---|

| Aa56 | m | |

| K | k | |

| R | r | the mouth, seen as a profile |

| I25 | ꜥq | |

| I24 | pr |

New alphabetic values for signs

The list of alphabetic signs was extended, mostly through the use of the consonantal principle : a multi-consonantal sign whose value contained one strong consonant and weak ones could be used to write this strong consonant.

For instance, siA, originally sꞽꜣ, can be used to write s. And F51, ꞽwf, to write f.

Of course, this system is exactly the one which gave the original alphabetic signs their values.

Things are a bit more complicated than that however:

- first, this system interacts with other factors. For instance, ib can have the value b and p. The first one is a straightforward application of the consonantal principle: “ꞽb” > “b” . The value p is the combination of the consonantal principle and phonetic confusion b/p (already visible in some ramesside texts).

- the origin can stem from a relatively unusual use of the sign. For instance, W10 often writes “ꜥ”; according to Fairmann, ASAE 43, the reason is its use as determinative in a:W10, “ꜥ”, bowl.

- the consonantal principle is not the only explanation ; graphical confusions, graphical plays, etc... can be involved.

| Sign(s) | value | comment |

|---|---|---|

| W10 | a | |

| M1 | m | from ꞽmꜣ |

| A9 | f | from fꜣꞽ |

| nw | n |

In the Dendera dedicatory inscriptions, different tree-sign are used to write m, in particular M46.

New values for old signs

Some signs acquire new values :

| Sign(s) | value | comment |

|---|---|---|

| xpr | t3, t | |

| P1 | ꞽm | from ꞽmw, boat |

| bit | kꜣ.t | (see below) |

| O123 | ẖnw | Ꞽṯ-tꜣ.wy is the “Royal Residence” by excellence |

Regarding bit = kꜣ.t, I don't fully understand why Fairman considers that he can't give a reason for this value. Admittedly, the metaphores about animal qualities are very often culturally grounded, but in this case, it seems quite transparent to me.

Animate signs holding something

It's important to have a close look at the details of signs, and in particular to the objects which an animated sign may hold. They may give the value of the whole sign, or be part of its reading.

For instance, in the BIFAO article, p. 97, the sign C9C (C9C) has the reading sḫm.

The sign value might be compositionnal : that is, the hieroglyph is a relatively free assembly of other signs whose reading can be combined. It is the case of E86 mꞽ rꜥ, combining the cat sign and the Rꜥ sign. For baboons, both E47 and E196 have the reading ꞽn : E35 ꞽ + N n, and E35 ꞽ + nw n(w),

Phonetic phenomena

During the whole history of the Egyptian language, many consonants, originally distinct, are more or less merged. We all know that the ṯ/t distinction was more or less lost as early as Middle Egyptian. Late Egyptian helps a lot here, because many of the “confusions” in Ptolemaic already occur in this stage of the language.

Hence, one can find the spelling g-R for ẖr, with g = g ≈ ẖ and R = r, or E17, originally sꜣb for sp (the ꜣ falls, and the b becomes p).

The consonants which are prone to confusion are:

- ꜥ,ꞽ,w

- b,p,f,m

- m,n

- t,ṯ,d,ḏ

- ḫ,ḥ,ḫ,ẖ

- š,ẖ

- q,g,k

Some cases are more likely than others. For instance, t,ṯ,d,ḏ is very usual, and g,q,k was already known in Late Egyptian.

ꞽw/r/ꞽr

The fall of final r had weird consequences in Late Egyptian orthography (especially in the XXth dynasty and later). The preposition r, when written in front of a substantive, was pronounced as a vowel. For instance, the Late Egyptian r-b-n:Z2-r-N31:D54, r-bnr (or r-bl, as n:Z2-r is a Late Egyptian writing for “l” ), corresponds to the Coptic “ⲉⲃⲟⲗ”. We have good reasons to believe that r in this context was already pronounced as a vowel in Late Egyptian. As a matter of fact, this is the reason why, when the preposition was written in front of a suffix pronoun (status pronominalis), the spelling would often double it: r:r*Z1-W-Z3A r=w6.

In the case of the preposition r, this lead to a general confusion between:

- r the preposition

- i-w the particle

- i-A2 the “prothetic yod”, found in front of some verbal forms, second tenses and imperatives

In the later part of Late Egyptian, one could be used for the other. In Demotic, r is regularly used as a spelling of the “prothetic yod”.

In the Dendera inscriptions, i-w can be used as a spelling of r, or it can have its initial value of ꞽw.

Graphical confusions

In the case of r and R, the value of the sign allowed to chose a different representation. However, in all stages of Egyptian, it's rather usual to find cases where similarities in the shapes of signs led to confusions, and to reinterpretations of sign shapes.

In Dendera, this is for instance the case of F107A (F107A) which has the value dmḏ and is a variant of dmD.

Note that the word confusion is a bit misleading. The confusions of signs with similar shapes is probably not a mistake of the hierogrammates. The word plays and etymologies we find in the glosses of religious texts show that they understood similarities as meaningful. Hence, those “confusions” were probably often a deliberate choice.

Thot, ibis and baboons

In late temples, the name of Thot is sometimes written i-nTr. It might seem weird, but the cause is relatively simple. Some very cursive hieratic rendering of the sign G26 look exactly like a hieratic i (Möller III, p. 19).

Conversely, a number of signs which represent Thot can be used to write the yod ꞽ, among those E35 and DHwty.

The baboon E35 has many possible values : nfr, ḏḏ, ꞽp, wp.... It shares the value nfr with other baboon signs like E53, E51, E32 and horses like E6A.

-

Cauville, Sylvie. 2012. Dendara. 15: Traductions. Le pronaos du temple d’Hathor: plafond et parois extérieures. Orientalia Lovaniensia analecta 213. Leuven: Peeters. ↩

-

Wilson, Penelope. 1997. A Ptolemaic Lexikon: A Lexicographical Study of the Texts in the Temple of Edfu. Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta 78. Leuven: Peeters. p. 229, gives the example wm.t sn.t=f m mḥ 5, the thickness of its foundations is 5 cubits. ↩

-

Johnson, Janet H. 2000. Thus Wrote ’Onchsheshonqy: An Introductory Grammar of Demotic. Third Edition. Studies in Ancient Oriental Civilization 45. Chicago: The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, p. 32 ↩

-

Neveu, François. 1996. La Langue Des Ramsès - Grammaire Du Néo-Égyptien. Paris: Khéops, p. 52 ↩

-

Leitz, Christian. 2002. Lexikon der ägyptischen Götter und Götterbezeichnungen. Orientalia lovaniensia analecta 110–116. Leuven Paris Dudley (Mass.): Peeters. ↩

-

Incidentally, the Middle Egyptian spellings of the preposition Hr-Z1, which is Hr:r in front of suffixes, has the same explanation. ↩